Originally published in the Bangor Daily News, September 23, 2025

In a lot of ways, I am probably a lot like you.

I am a middle-aged, married white guy with a mortgage and a modest home in a quiet residential neighborhood with well-manicured lawns and friendly neighbors.

I love living in Maine. I have two grown children. I adore my dog, and I am blessed to have many good friends. I fret about rising property taxes, and it feels as if I am eternally engaged in thermostat battles with my wife.

I work hard, follow the law and pay my taxes. I drive a late-model Chevy Silverado pick-up truck and enjoy camping at both Rangeley and Moosehead lakes.

But there is another part of me that you would likely never guess unless I told you.

From the outside, my life may look almost idyllic or at least average, run-of-the-mill, but I have to work to maintain this stability and my outward appearance.

For more than 40 years, I have struggled with a wide range of mental health issues, from bi-polar depression and severe anxiety to raucous bouts of schizoid-affective disorder.

I recognize and accept my responsibility to manage my mental health, but it’s not always easy. Some of the medications I take affect everything from my libido to my weight. I am one of the lucky ones, I have a good psychiatrist. I also participate in regular counseling with a therapist. My insurance covers the bulk of my prescription costs.

Although hidden from the public view, there is a toll, and I sometimes feel as if my illness is a burden on my family, especially my wife, who is my greatest support and the person who ensures that I am taking my meds as prescribed.

As a young adult in my early 20s, I struggled with stability on every level. My employment was erratic. The few relationships I had were chaotic. At three different times, I found myself homeless, living on the proverbial outer edge of society.

I was reluctant to take medications. I did not want to be controlled or – as I saw it – poisoned by society. I did a lot of couch surfing. I even landed in jail for assaulting a police officer.

I was in and out of various psychiatric facilities both on a voluntary and involuntary basis. I got in trouble with the Secret Service for talking about what I would like to do to President Reagan in 1984.

Flash forward more than 40 years.

Just like you, I was shocked, saddened and angry about the brutal, senseless killing of a young woman on a commuter train in Charlotte, North Carolina last week.

She did not deserve that fate. Her family did nothing to warrant such tremendous loss and heart-breaking grief.

How do we comfort them? How do we reconcile the fact that millions of Americans are living on the edge of society, saddled with a significant illness and a stunning lack of resources?

How do we handle our anger? Our resentment?

Sadly, I do not have any answers. I know that my friends on the political right talk a good game about mental illness in the wake of every mass shooting, but then suddenly get quiet when it comes to legislation that requires increased funding for mental health services.

Just like you, I was shocked, saddened

and angry about the brutal, senseless

killing of a young woman on a commuter

train in Charlotte, N.C. last week.

Meanwhile, my friends on the political left talk a lot about community-based care, often forgetting that there are some people who need to be involuntarily hospitalized.

While I do not have any answers, I do know this: we cannot afford to sacrifice our humanity and our shared sense of decency and compassion.

Our national dialogue has become so vitriolic that a major television network commentator can publicly suggest involuntary euthanasia for homeless people who refuse mental health treatment.

Think about that for just a minute or two.

Set aside the 14th Amendment if you need to.

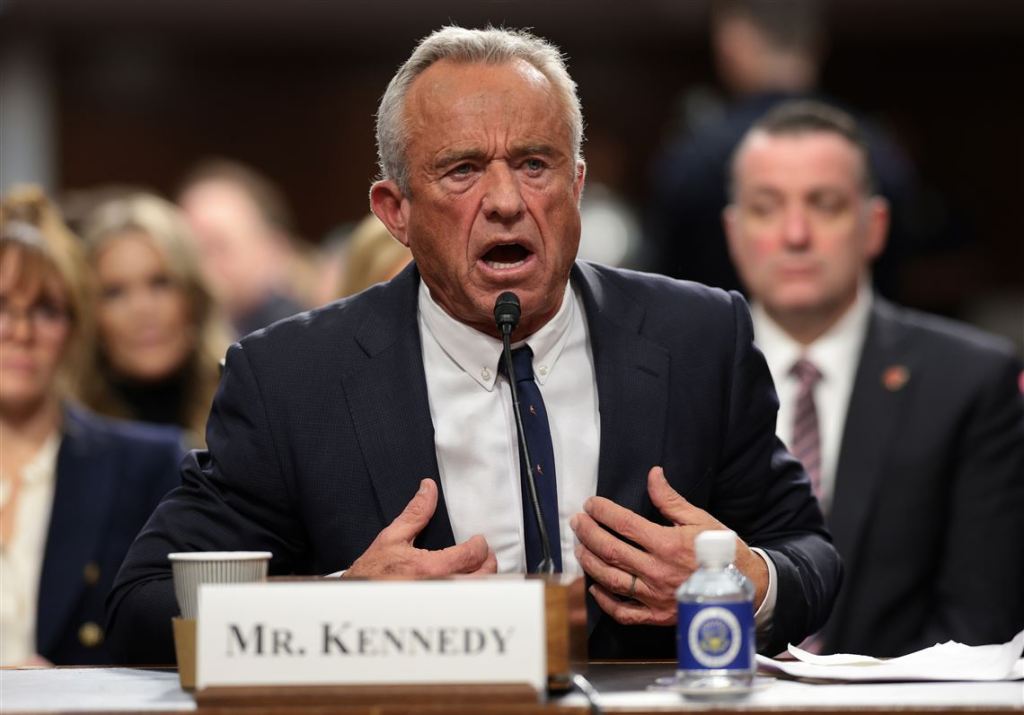

There is a large group of people in this country who heard Mr. Kilmeade’s statements and simply shrugged.

I was a homeless person who often refused treatment. Did I deserve to be put to death for refusing to take medications?

Have we fallen so far that we are now willing to even entertain the notion of rounding up and killing some of our most vulnerable citizens?

If so, just remember that so-called solution will require rounding up people who look and act a lot like you and me.

_________________

Randy Seaver is the editor and founder of the Biddeford Gazette. He regularly blogs on issues regarding mental health and his own journey toward recovery. E-mail randy@randyseaver.com