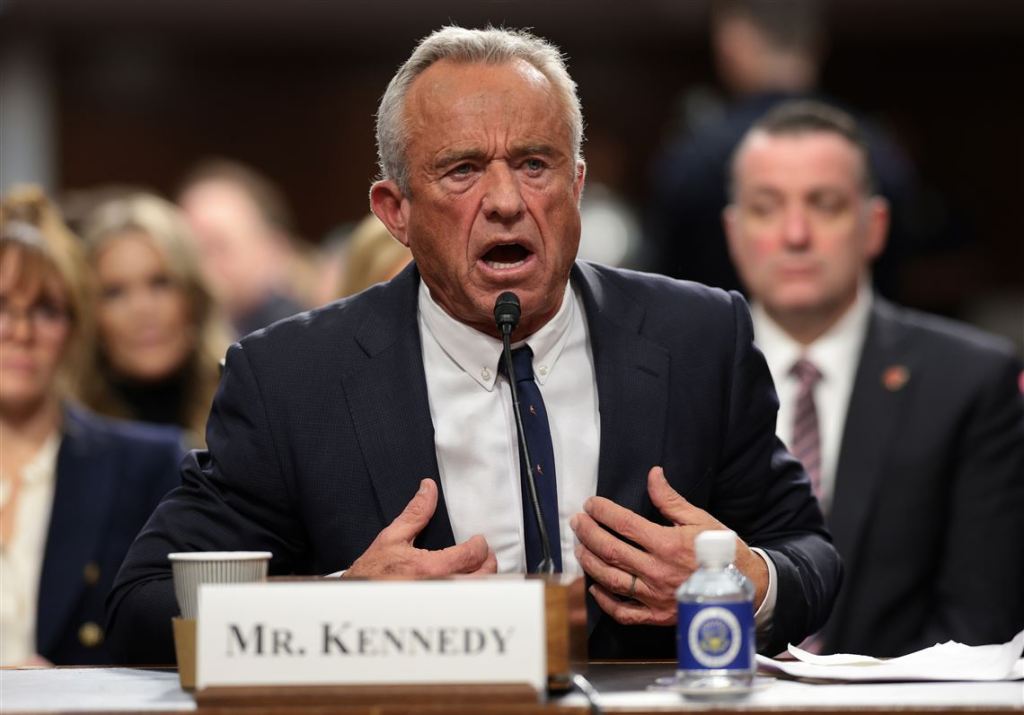

There was a time when I had tremendous respect for former Portland Press Herald Reporter Ted Cohen.

But given some of his recent screeds as a contributing columnist for the Maine Wire, I am now forced to reevaluate my prior opinion of the veteran journalist who earned an enviable reputation as a hard-working, tenacious, boots-on-the-ground reporter.

In fact, I think I should be retroactively tested for rampant drug abuse that distorted both my judgment and world view.

As is common knowledge in Maine’s rather incestuous community of former and current journalists, the Press Herald gave Cohen the boot several years ago, following an internal argument regarding a scoop he uncovered about George W. Bush’s youthful indiscretions near the Bush family’s summer compound in Kennebunkport.

Cohen wrote a book about it, and then promptly earned his CDL license — gave up typing and covering tedious town council meetings — all for the better working hours of being a commercial truck driver.

Now — nearly 30 years later — Cohen has seemingly rebounded and is today penning an occasional column for the Maine Wire, a digital publication that matches Cohen’s unapologetic style for making government officials and the beautiful people squeamish.

But Cohen — with every opportunity he gets — routinely floods Facebook and other social media outlets with rampant complaints about his former employer, the Press Herald, Maine’s largest daily newspaper.

Tainted Love | When journalistic envy raises its ugly head

Cohen – despite his vicious critiques — is not just somewhat obsessed with his former employer. It seems that he is also a bit fixated on yours truly.

Cohen and I were colleagues and competitors back in the mid-1990s, when I was then working for the weekly Biddeford-Saco-OOB Courier.

Our offices were located about 75-feet apart on Main Street in Biddeford, until the Press Herald opted to shutter their regional Biddeford bureau several years ago.

Ted and I got along nicely. I looked up to him as a more experienced and wiser competitor. He sort-of took me under his wing and offered me lots of sage advice.

But that all came to a screeching halt about two years ago.

Examples of Cohen trolling my social media accounts are almost too numerous to count. (I suck at math as much as I suck at writing).

A couple of years ago, Cohen sent me an email strongly suggesting that I quit blogging about my struggles with a significant mental illness.

“You should just shut-the-fuck up on social media and go back to being a full-time journalist covering the city of Biddeford,” Cohen wrote. “Nobody really cares about that crap.”

He also described me last year as “a Facebook blogger,” revealing that he has a rather loose grasp on the subtle differences between posting on Facebook and blogging.

Somehow, Cohen missed the fact that I had launched the Biddeford Gazette — a non-profit, digital media outlet — several weeks prior to his latest rant about me and my lack of journalistic ethics.

But here’s something really strange.

Despite my lack of journalistic ethics and the amateur nature of my latest endeavor – Cohen saw fit to submit a guest column about the city of Biddeford . . . in the Biddeford Gazette — just a few months ago.

Cohen, apparently, is a regular reader and subscriber of the Gazette.

Irony or the vulnerabilities of old age?

What’s the Buzz, Ted?

Cohen’s latest shot across my bow happened just a few weeks ago in a rambling essay he wrote for the Maine Wire about a “newspaper war” here in the city of Biddeford.

Cohen’s reporting about this so-called war lacked both cohesion and common sense, leaving several glaring omissions of fact and nearly zero context.

Any editors on duty? (A favorite Cohen quip about the Press Herald).

For all of his wailing and gnashing of teeth about journalistic integrity, Ted let his emotions trump his reporting. It’s okay. It happens to the best of us sometimes.

For example, Ted only mentions one side in this alleged “newspaper war.” Kinda the equivalent of saying, “Someone bombed Iran, but fuck the details.”

Apparently, Ted is too insecure to mention my name or the name of my publication.

Cohen describes the Biddeford Buzz, a relatively new media upstart as “wildly popular” in the Maine Wire’s headline. In reading the unapologetic hit piece, it becomes clear that Cohen justifies “wildly popular” by the number of people who “follow” the Buzz on Facebook.

Disclosure: The Biddeford Buzz – only seven months old – has more than double the number of followers of the Biddeford Gazette (2.1k).

I cannot accurately reveal the number of people who follow the Biddeford Buzz. They have me blocked from seeing their Facebook page.

Using Cohen’s logic, does that mean that I am more than 16 times as friendly as Ted Cohen because I have nearly 2,200 Facebook friends compared to the 123 people who follow Cohen on Facebook, where he describes himself as a “digital creator?”

In his hit piece, Cohen makes no bones about the fact that he was unable to determine (or reveal) who exactly is behind the Biddeford Buzz — even though it is rather common knowledge in Biddeford.

If you visit the Biddeford Buzz website, you will note that they are trying really hard to be a lot like the Biddeford Gazette, though the bulk of their “content’ is reserved for their Facebook feed.

There are, however, a few key — perhaps nuanced — differences between the two digital publications.

- The Gazette uses bylines and attribution in all of our stories;

- The Gazette tries to steer clear of ‘cutting and pasting” press releases, and then passing them off as “news;”

- The Gazette has editorial oversight, years of professional experience and training – not to mention published editorial policies;

- The Gazette provides its readers with clear, easy-to-find information about the people behind our publication;

- The Gazette is incorporated as a non-profit media outlet with the state of Maine.

Finally, the Gazette actually publishes obituaries on the tab labeled as “Obituaries” on our website.

All of these points somehow fail to cause Cohen concern or hesitation in talking about Biddeford’s new “dominant news source.”

I get why Cohen is excited about the Biddeford Buzz. In fact, I recently wrote a fairly glowing piece about the Biddeford Buzz and its founder Josh Wolfe.

I opined that the Biddeford Buzz serves a valuable role in my hometown, providing Biddeford people a viable alternative to the status quo of local journalism.

Apparently, I have enough reporter curiosity to ferret out who is actually behind the Buzz, another individual who really does not like me and trolls my social media accounts.

If Cohen bothered to actually visit Biddeford again, he could find Wolfe sitting in the front row at almost every city council meeting.

Both Cohen and Wolfe may be interested to know that I will soon — once again — be teaching my Introduction to Journalism class via the Biddeford-Saco-OOB Adult Education program. They be interested in a refresher course?

I still like Ted. I just don’t trust him.

Hey, Maine Wire – any editors on duty?

________________

ABOUT THE AUTHOR | Randy Seaver is a nearly insufferable malcontent living in Biddeford, Maine. He is a veteran journalist and a jazz aficionado. He is also the editor and founder of the Biddeford Gazette, a non-profit digital media outlet that focuses on the city of Biddeford. Send your praise, angry comments or inquiries about journalistic ethics to randy@randyseaver.com

Subscribe for free . . . it’s worth it

FOLLOW: