At the risk of provoking law enforcement officers, irate taxpayers, members of Maine’s Legislature and people who suffer with a mental illness, I want to congratulate Tux Turkel and a his team at the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram for an exceptional article in this morning’s paper.

At the risk of provoking law enforcement officers, irate taxpayers, members of Maine’s Legislature and people who suffer with a mental illness, I want to congratulate Tux Turkel and a his team at the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram for an exceptional article in this morning’s paper.

At the crux of the story is the number of fatal shootings in Maine that are connected to police calls that involve someone who is mentally ill.

Before we proceed further, it’s important to note that the vast and overwhelming majority of people who suffer from a mental illness never have an interaction with law enforcement agencies.

Secondly, despite the myths, stigma, Hollywood hype and media bias, the overwhelming majority of mentally ill people are not violent.

In fact, violent acts committed by people with serious mental illness comprise an exceptionally small proportion of the overall violent crime rate in the U.S. They are more likely to be the victims of violence, not its perpetrators, according to the National Association of Social Workers (NASW)

In its March 2011 article, “Budgets Balanced at Expense of Mentally Ill,” the NASW newsletter also mentions a new report by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration that documents a nationwide decline in behavioral health care spending as a share of all health care spending, from 9.3 percent in 1986 to just 7.3 percent, or $135 billion out of $1.85 trillion, in 2005.

(See: Pocketful of Kryptonite; All Along the Watchtower, April 2011)

Mental illness is an uncomfortable subject, one which many people would like to ignore and sweep below the rug. But we ignore it at our peril.

Asking law enforcement officers to effectively deal with ill people is sort of like expecting school janitors to provide high school tutoring services.

In our current situation, there is a natural tendency to blame the survivor. If someone has a knife and they begin moving toward you in a threatening manner, don’t you have the right to defend yourself?

Or do we blame the person holding the knife, a person with a mental illness who is unable to comprehend reality when it matters most?

Try to imagine what it’s like to be the cop who is forced to deal with that situation, to live the rest of his or her life with the knowledge that he/she ended another person’s life.

According to the newspaper: Since 2000, police in Maine have fired their guns at 71 people, hitting 57 of them. Thirty-three of those people died. A review of these 57 shootings by the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram found that at least 24 of them, or 42 percent, involved people with mental health problems. Seven of the shootings were alcohol-related. Two involved drugs.

Of the 33 people who were killed, at least 19, or 58 percent, had mental health problems.

In the days following the 2007 massacre at Virginia Tech, “Nightly newscasts reported “no known motive” and focused on the gunman’s anger, sense of isolation, and preoccupation with violent revenge. No one who read or saw the coverage would learn what a psychotic break looks like, nor that the vast majority of people with mental disorders are not violent. This kind of contextual information is conspicuously missing from major newspapers and TV,” wrote Richard Friedman in “Media and Madness,” an article published in the June 23, 2008 issue of The American Prospect.

Friedman goes on to explain that “Hollywood has benefited from a long-standing and lurid fascination with psychiatric illness,” referencing movies such as Psycho, The Silence of the Lambs, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Fatal Attraction.

According to Friedman, “exaggerated characters like these may help make “average” people feel safer by displacing the threat of violence to a well-defined group.”

So, should we blame lawmakers or Hollywood movies for rather weak funding and policies to assist law enforcement officers in addressing the complications of dealing with mentally ill individuals?

Or maybe, should we all take a good, long look in the mirror? In an age of economic recession, we must wrangle with legislative spending priorities.

But consider how expensive and grossly inefficient our current system is when it comes to dealing with potentially violent people who suffer from a mental illness.

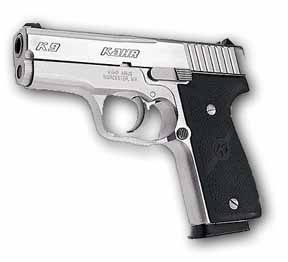

In November 1993, I was living at my sister’s home near Augusta. Two days earlier, I purchased a used Lorcin .380 semi-automatic handgun with the intention of committing suicide. Fortunately, the gun misfired and jammed. Within moments, it seemed, my sister’s home was surrounded by a cadre of police officers, armed to the teeth. Who could blame them?

I was eventually transported to the Jackson Brook Institute (today Spring Harbor Hospital), where I was involuntarily committed for several days.

Compare that situation to one in 1986, when I was living in Tucson, Arizona. Pima County had a mental health rapid response team that included trained mental health workers. These teams served as the lead for responding to crisis situations. They could effectively assess the situation and call police only when necessary. They were equipped to provide the police with tools, intelligence and situational analysis that kept the officers safe.

Those types of programs cost money, but they also save taxpayers money over the long-term. More importantly, the approach in Tucson is far more likely to yield results in which no one dies. But how do you calculate the financial worth of preventing a fatal shooting?

Great article Randy. My entire family has been and still is associated with Sweetser. Mental illness is a major problem that can not be swept under the rug

LikeLike